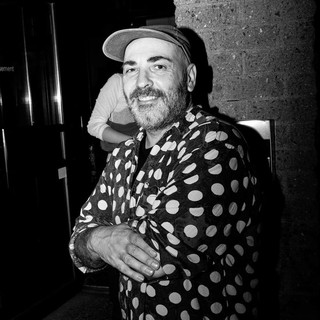

CHATEAUX MACABRE — The World of Robert Dela Cruz Hurt

- Milan Tanedjikov

- Dec 8, 2025

- 5 min read

A design profile exploring Robert Dela Cruz Hurt’s cultural storytelling, Filipino ancestry, and contemporary fashion language within the LIGNES DE FUITE Mentoring Program.

There are designers who build silhouettes, and there are designers who build universes. Robert Dela Cruz Hurt does both — sometimes with a joke, sometimes with an ancestral echo, sometimes with a meme so specific that only chronically online Filipinos will understand. His creative world sits somewhere between emo adolescence, Ifugao, Jack Victor wool trousers, and the quiet confidence his mother once named without realizing she was defining his future brand DNA.

Robert grew up in Montréal, but the Montréal he inhabited changed dramatically throughout his childhood. First, Côtes-des-Neiges — a Filipino-dominated neighbourhood whose sense of immigrant hustle and collective humour shaped him before he even understood why. Then, Côte-Saint-Luc — quieter, more insulated, Hasidic, distant from the chaotic warmth he associated with home. He jokes that the metro line between Namur and Snowdon looks like Gotham to some, but to him it has always felt like safety.

It was in these environments that his cultural codes rooted themselves:be proud you’re Filipino. Don’t forget where you came from. Carry the jokes with you.

And his family gave him more than roots — they gave him mythology. His father comes from the Ifugao, an Indigenous community so culturally powerful their traditions are protected by UNESCO. His mother’s lineage, meanwhile, carries the other half of his identity: a grandfather who was a GrandMaster Mason. It makes complete sense that Robert’s eventual brand ideas would merge shamanism and architecture. Chateaux Macabre wasn’t chosen for aesthetic reasons; it was already written in his bloodline.

But before any of this became fashion vocabulary, there was his mother — always the first influence. She worked at Jack Victor, and when 13-year-old Robert visited her office, it felt to him like stepping into “an Italian Willy Wonka factory.” Blazers hanging from the ceiling, patterns everywhere, the hum of tailoring studios. She walked him through the floors with authority — a Filipina woman working in administration in a Montréal tailoring house — and Robert felt something anchor inside him.

He remembers Mario Rotta, an older Italian designer, stopping him only to compliment his pants. The irony is that those pants were Jack Victor wool trousers he had badly hemmed himself. The compliment stayed. So did the feeling that fashion wasn’t frivolous. It was a way of learning how life is constructed.

Still, adolescence called for rebellion. While his mother dressed him in quiet tailoring, Robert lived his peak swagapino era: snapbacks, oversized plastic glasses, fox tail keychains, 2014 graphics, a portable CONSEW sewing machine for hemming. He was emo, into occult conspiracies, early Kanye, and Reddit rabbit holes. When he wasn’t online, he was drawing. He expresses it simply:

“I never rejected fashion. It was just my way toward understanding the world.”

The tension that defines him today — humour versus darkness, extrovert versus introvert, architecture versus shamanism — existed even then. He calls his extroverted persona Mr. h u r t, a version of himself that steps forward impulsively, performatively, when emotions run high. But the interior self — the one building ancestral cathedrals out of memories — is

Chateaux Macabre.

His work is influenced by everything he is: Filipino ancestry, excellent textiles, Kanye’s delusional confidence, Rick Owens' quiet edits, Virgil Abloh’s historic breakthrough, Martine Rose’s cultural specificity, BOTTER’s diasporic intelligence, Wales Bonner’s intimacy, and the raw emotional texture of Chet Baker. His references move fluidly between the high and the deeply unserious: Machiavelli, Dostoevsky, gothic cathedrals, Filipino painters Juan Luna and Fernando Amorsolo, the political fire of José Rizal, Twitch-streamer humour, fashion subreddits, emo music, male manipulator memes.

When asked what his aesthetic is, he answers:

“Niche confidence.”

Not niche for obscurity, but because his clothes speak directly to the version of himself who once searched for Filipinos in fashion and found none. He designs to tell that 13-year-old boy: you were never supposed to fit into their archetypes — you were meant to make your own.

Robert’s cultural lens is not decorative. He speaks of Filipino excellence with sincerity, insisting that Filipino youth deserve to see themselves in narratives beyond stereotypes. His work is humorous but never flippant; dark but never bleak. “My work can scream outgoing but has a quiet taste of silence,” he explains. He dresses like someone always prepared for a funeral — yet cracking jokes on the way there.

His storytelling is situational and world-based. He imagines entire universes to house his collections.“What if the Philippines was a global fashion capital?” he asks.Not as fiction — as possibility.

Earlier this year, Robert traveled back to the Philippines — a trip that re-oriented everything. It wasn’t his first visit, but it was the first time he felt he wasn’t a tourist. His uncle, a retired three-star general, had previously required the family to travel with an escort for safety. This time, stripped of that barrier, Robert found himself blending into the crowd in a way that felt both surreal and clarifying.“The feeling of seeing people who look like me,” he says, “is crazy.”

What he brought back from the Philippines is now shaping his newest project: a fusion of Filipino-Canadiana, coronation iconography, swagapino humour, Spanish-gothic architecture, European brutalism, and diaspora longing. He is exploring belonging, delusion, ancestral pride, meme culture, and the audacity to believe that the Philippines could one day occupy a place in fashion history. His method begins with feeling, then images — often memes — and always a tie to his roots. “If I can tie it to my roots,” he says, “it was meant for me.” He works from laughter and seriousness equally, insisting they are not opposites but collaborators. A deadpan joke delivered with precision is, to him, couture.

Looking forward, Robert sees multiple brands emerging from his universe — one shamanic and architectural (Chateaux Macabre), one humorous and unhinged in a deadly serious way (the Mr. h u r t ecosystem). He imagines a production house in the Philippines, a global presence, and a place in fashion history defined not by imitation but by cultural invention.

His ambition is not shy: “I want to change the Philippines. I want to show the world Filipino excellence.”

And he works with urgency — a principle given to him by a beloved LaSalle instructor:

“There are only solutions.”

He carries that line like an ancestral spell.

Credits:

Images Robert Dela Cruz Hurt Words Milan Tanedjikov

As he develops this vision inside the LIGNES DE FUITE Mentoring Program, Robert will present early explorations of his universe at the Design Research Exhibition on December 19, during Crossfade, co-organized with Gabriela Hébert and Narrativ. It will be the first time the multiple selves of Robert — the emo kid, the tailor’s son, the Ifugao descendant, the swagapino joker, the architect of haunted houses — step into public view as one coherent, daring designer.

Comments